Assessment of whiplash injury

Practitioners should take a history from the patient irrespective of the whiplash associated disorder grade (WAD) grade (1)

At the initial visit practitioners should:

- classify the WAD grade using the Quebec Task Force Classification (QTF)

- assess pain using the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS)

- assess disability using the Neck Disability Index (NDI)

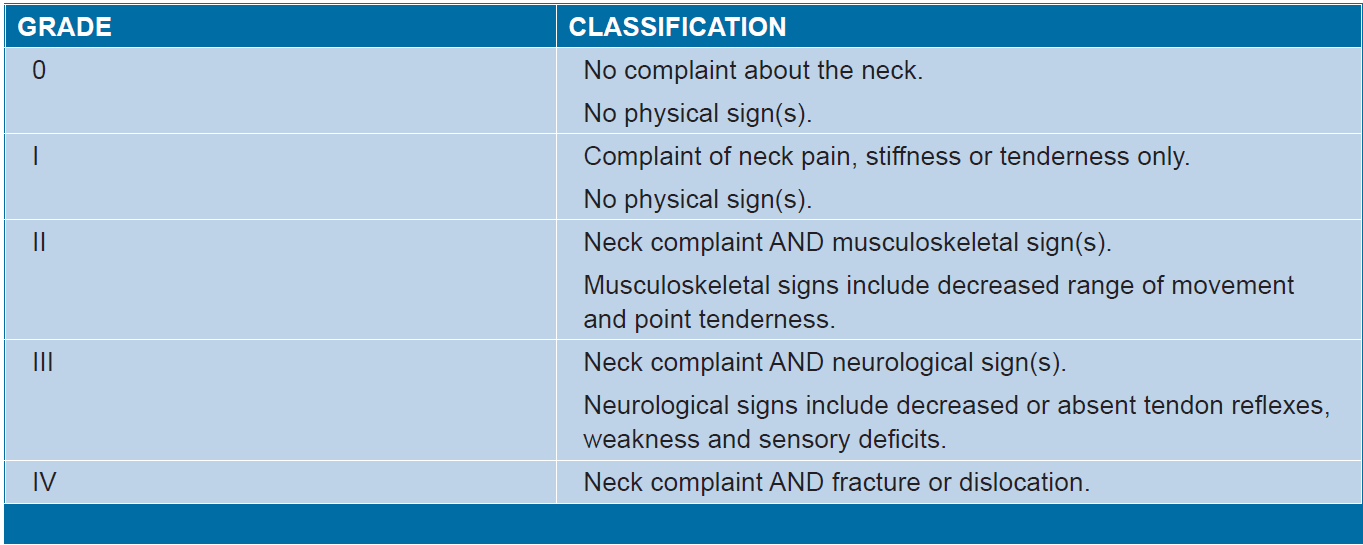

Quebec Task Force Classification of whiplash-associated disorders

Whiplash-associated disorders (WAD) can be classified into four grades:

Grade IV is only considered to the extent of diagnosis of the condition and immediate referral to an emergency department or appropriate medical specialist (1)

- at initial assessment - relevant information including:

- circumstances of the injury e.g. type of collision, whether loss of consciousness, safety factors such as if wearing seatbelt

- symptoms - localisation, time and profile of onset, intensity of pain (ideally assessed using the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS))

- occupational history (2)

- medical history, including previous injury or infection; history of relevant medical conditions e.g. rigid spinal disease such as ankylosing spondylitis, history of cancer, treatment with medication associated with fragility fractures such as chronic corticosteroid use

- anxiety or depression (2)

- presence of fever (2)

- at each visit practitioners should conduct a focused physical examination

- at initial assessment:

- do not examine neck movements until clinical features which may indicate a serious injury have been excluded. If a serious neck or head injury is suspected, urgently refer to Accident and Emergency.

- clinical features that indicate a possible serious neck injury

- features of a serious head or neck injury include:

- altered level of consciousness

- a focal neurological deficit or paraesthesia in the extremities

- midline cervical tenderness

- risk factors for serious injury include (2):

- onset of neck pain immediately following the event

- aged >=65 years

- drowning or diving accident

- multiple fractures

- presence of significant head or facial injury

- dangerous mechanism of injury (a fall greater than 1 metre) or a side impact collision

- rigid spinal disease (for example, ankylosing spondylitis)

- unable to walk about, or sit following the injury

- features of a serious head or neck injury include:

- clinical features that indicate a possible serious neck injury

- do not examine neck movements until clinical features which may indicate a serious injury have been excluded. If a serious neck or head injury is suspected, urgently refer to Accident and Emergency.

- at initial assessment:

- at the initial visit practitioners should use the Canadian C-Spine Rule to:

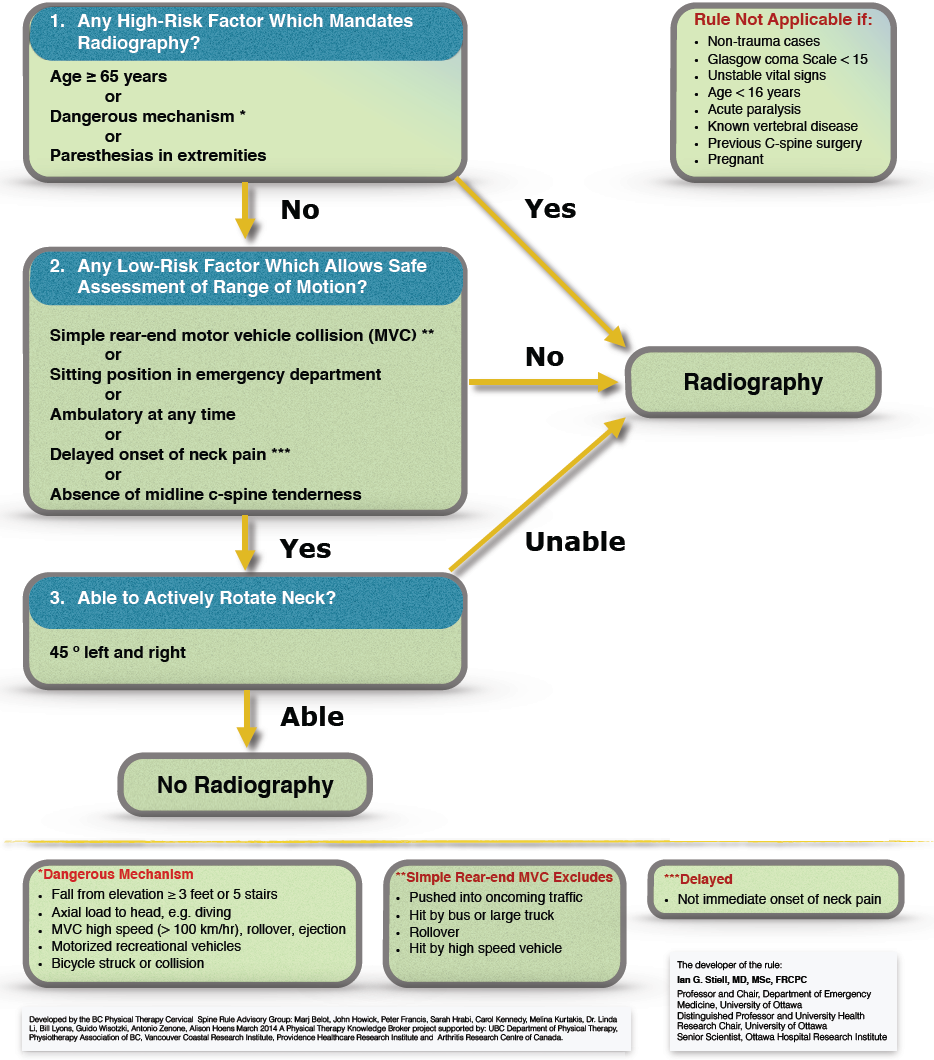

- determine whether X-ray of the cervical spine is required for diagnosis of fracture or dislocation and to avoid unnecessary exposure to X-rays Refer people at high risk of serious injury for cervical spine radiography Apply the Canadian C-spine rule in people aged 65 years or under to determine whether X-ray of the cervical spine is required for diagnosis of fracture or dislocation: Instructions for using the Canadian C-Spine Rule The Canadian C-Spine Rule is applicable to patients who are in an alert (Glasgow Coma Scale score of 15) and stable condition following trauma where cervical spine injury is a concern. It is not applicable in non-trauma cases, if the patient has unstable vital signs, acute paralysis, known vertebral disease or previous history of Cervical Spine surgery and age <16 years.

1. Define whether any high risk factors are present such as age (>=65 years) or dangerous mechanism (includes high speed or roll over or ejection, motorised recreation vehicle or bicycle crash). If this is the case, an X-ray of the cervical spine should be performed.

2. Define low risk factors that allow safe assessment of neck ROM. If the low risk factors shown in the flow chart are not present, an X-ray of the neck should be performed.

3. Assess rotation of the neck to 45 degrees in people who have low risk factors shown in the QTF Classification of Grades of WAD. If people are able to rotate their neck to 45 degrees, they do not require an X-ray of the neck.

This rule has been validated across several different populations and has been shown to have a sensitivity of 99.4 per cent and a specificity of 42.5 per cent. Essentially, physicians who follow this rule can be assured that a fracture will not be missed (95% CI 98-100%) (3). Further a systematic review investigated the diagnostic accuracy of the Canadian C-Spine Rule and the National Emergency, X-Radiography Utilization Study (NEXUS) criteria and found that the Canadian C-Spine Rule had better accuracy (4)

- do not use specialised imaging techniques, for example computed tomography (CT) scan, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in WAD grades I and II. Only use specialised imaging techniques for selected patients with WAD grade III, for example suspected nerve root compression or spinal cord injury (1)

- do not use specialised examination techniques (for example EEG, EMG and specialised peripheral neurological tests) in patients with WAD grades I or II. Only use specialised examinations in selected patients with WAD grade III, for example patients with suspected nerve root compression (1)

Reference:

- NSW. Guidelines for the management of acute whiplash-associated disorders for health professionals, third edition 2014

- CKS. Neck pain - whiplash injury (Accessed 3/11/19)

- Stiell, I. G., C.M. Clement, R.D. McKnight, R. Brison, M.J. Schull, and B.H. Rowe, The Canadian C-spine rule versus the NEXUS low-risk criteria in patients with trauma. New England Journal of Medicine, 2003. 349(26): p 2510-2518.

- Michaleff, Z.A., C.G. Maher, A.P. Verhagen, and T. Rebbeck, Accuracy of the Canadian C-spine rule and NEXUS to screen for clinically important cervical spine injury in patients following blunt trauma: a systematic review. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2012. 184(16): p. E867-E76

- https://www.physio-pedia.com/Canadian_C-Spine_Rule (Accessed 3/11/19)

Related pages

Create an account to add page annotations

Add information to this page that would be handy to have on hand during a consultation, such as a web address or phone number. This information will always be displayed when you visit this page